Resilia Special Report: How Nonprofits and Grantors are Directing Resources in a Time of Crisis

Download the full 21-page report

If we had to draw a single lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic, it would be that we’re all in this together. It’s hard to remember a time when we were more aware of the contributions made by our neighbors and fellow citizens. We’ve discovered that the term “essential worker” doesn’t just include hospitals and nurses, but cleaning staff, cashiers, people who work in manufacturing plants and distribution centers, and so on. We’ve been reminded that our everyday actions can have a huge impact on other people.

And we’ve seen how vital the nonprofit sector is to millions of Americans who can’t get the support they need from the government or anywhere else. For example, consider the long lines at food banks where families wait for hours to pick up a few days of groceries to feed their loved ones. By delivering food to families in need, nonprofits don’t just address hunger in our communities – they reduce the spread of COVID-19.

Catastrophes like COVID-19 realign priorities in a hurry. Many of the most serious problems that the nonprofit sector faces, such as anemic budgets, a lack of digital literacy, and a failure to track and report outcomes, have become all the more pressing over the past few months. And nonprofits themselves aren’t the only ones with weaknesses– grantors have their share of problems as well, such as poor communication, the failure to fully reimburse organizations for the work they do, and haphazard reporting and compliance processes.

However, nonprofits and grantors are taking significant steps to address these issues – COVID-19 just might have quickened the pace. We created this report to take a closer look at these developments and what they mean as the sector grapples with today’s crisis and prepares for the future.

Part 1:

HOW ARE NONPROFITS MANAGING CAPITAL?

When a charitable foundation, government, company, or any other grantor is considering how to use its resources as productively as possible, its first question will be: which nonprofits are worth investing in? To answer this question, grantors consider a wide range of measures: the effectiveness of an organization’s programs, how well it manages its finances, workforce, and other assets, its growth potential, and so on. In other words, what resources does a nonprofit have and how is it putting them to use?

Grantors are concerned about more than just projects – they want to know how sustainable the work is, what its strengths and weaknesses are, and ultimately whether it will be a responsible steward of the investments it receives. While this means nonprofits are under pressure to operate more efficiently and improve their reporting mechanisms, it also gives them an opportunity to distinguish themselves in an increasingly crowded sector (the total number of nonprofits in the U.S. increased by 10.4 percent between 2005 and 2015 – a proportion that’s only continuing to rise). A higher standard of expectations among grantors is a powerful incentive for nonprofits to streamline their operations, communicate more openly, and hold themselves (and their grantmaker) accountable. However, nonprofits should also seek to improve their capacities and scale impact as ends in and of themselves.

How nonprofits manage their resources is a particularly pressing issue considering the fact that many organizations operate on ultra-thin margins that make them especially vulnerable to major societal shifts like COVID-19.

NONPROFIT OPERATING RESERVES

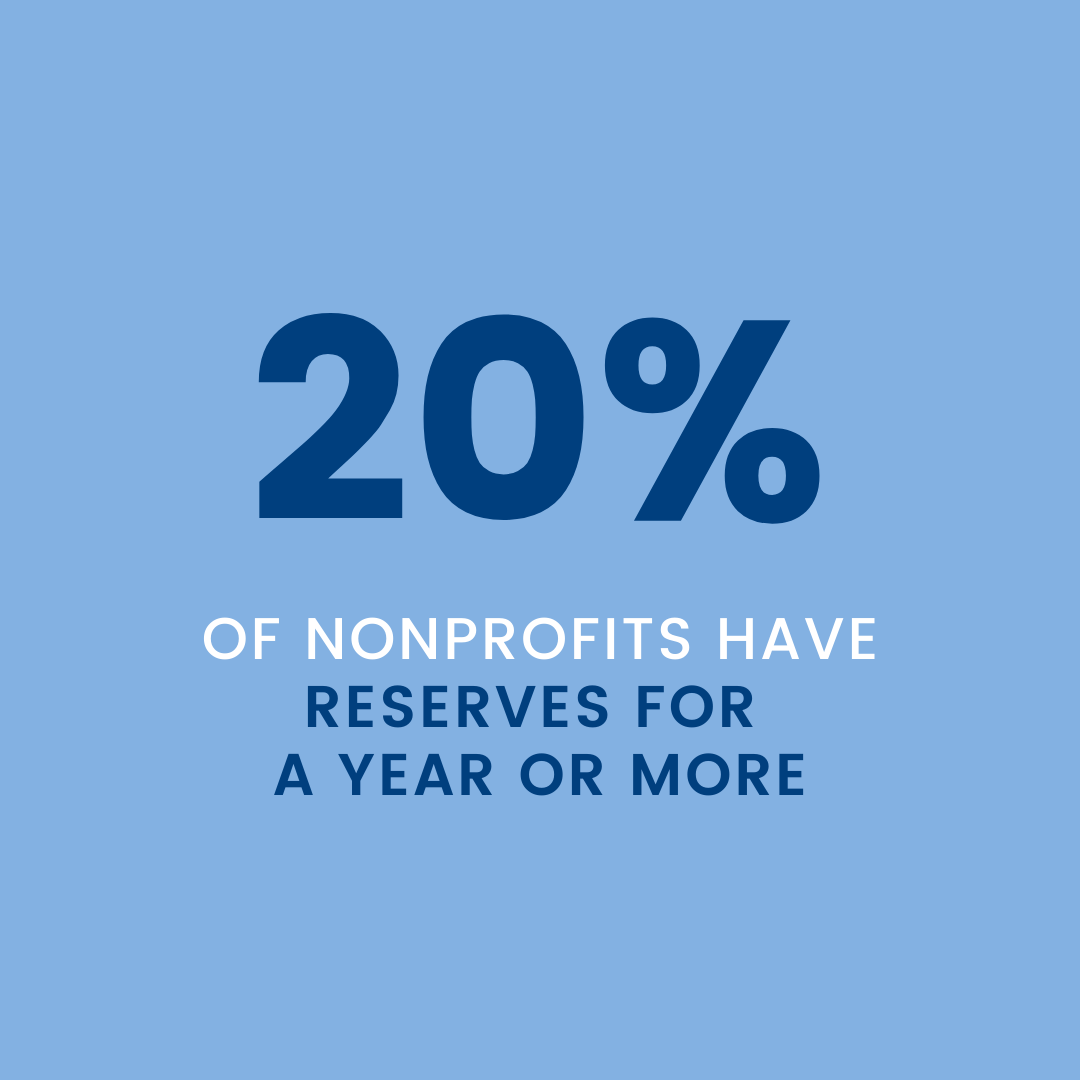

According to a recent study by BDO and The Nonprofit Times, just 20 percent of nonprofits have operating reserves for a year or more; 27 percent have reserves for six to 12 months; 40 percent have reserves for one to six months; and 13 percent have no reserves at all. On average, nonprofits have less than nine months of operating reserves.

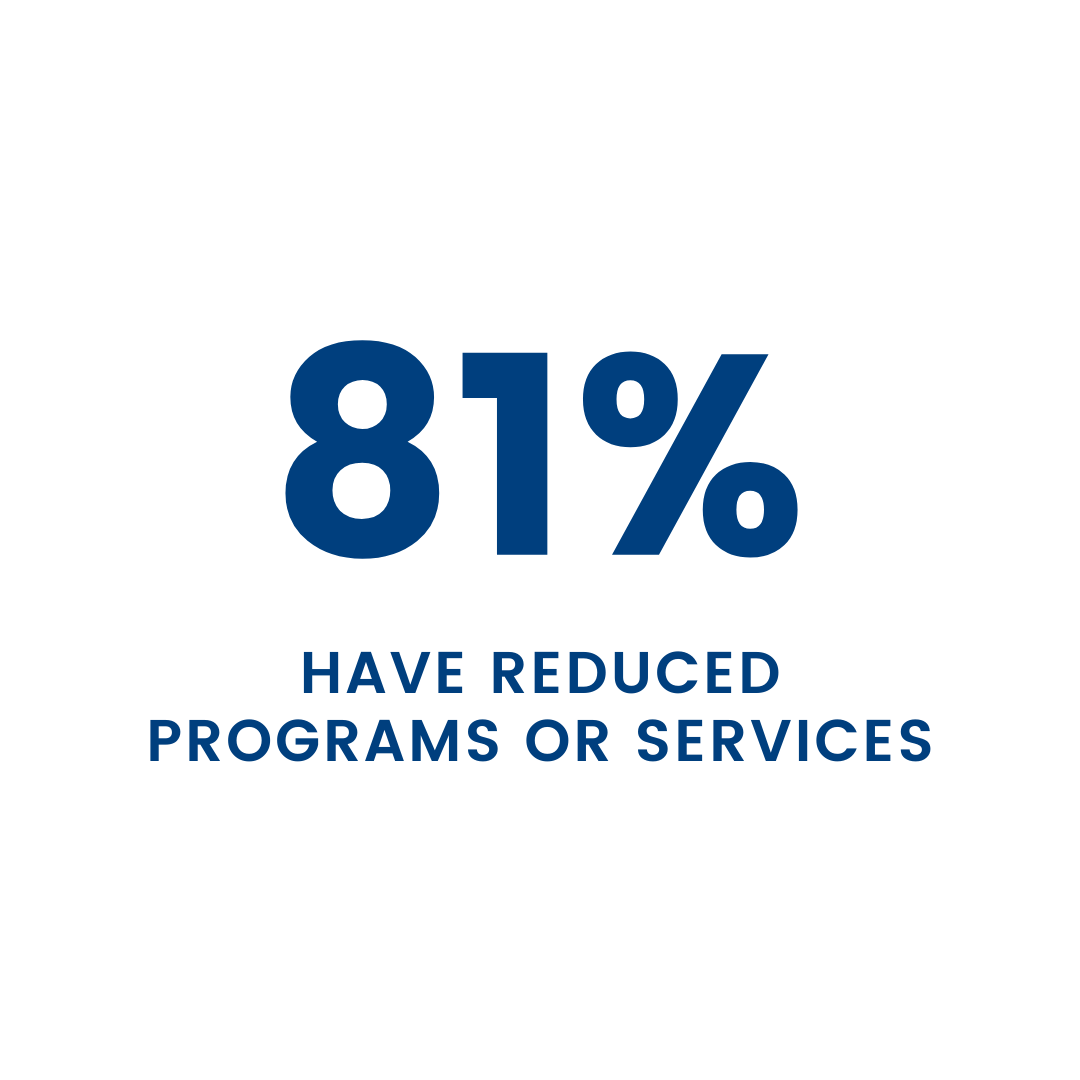

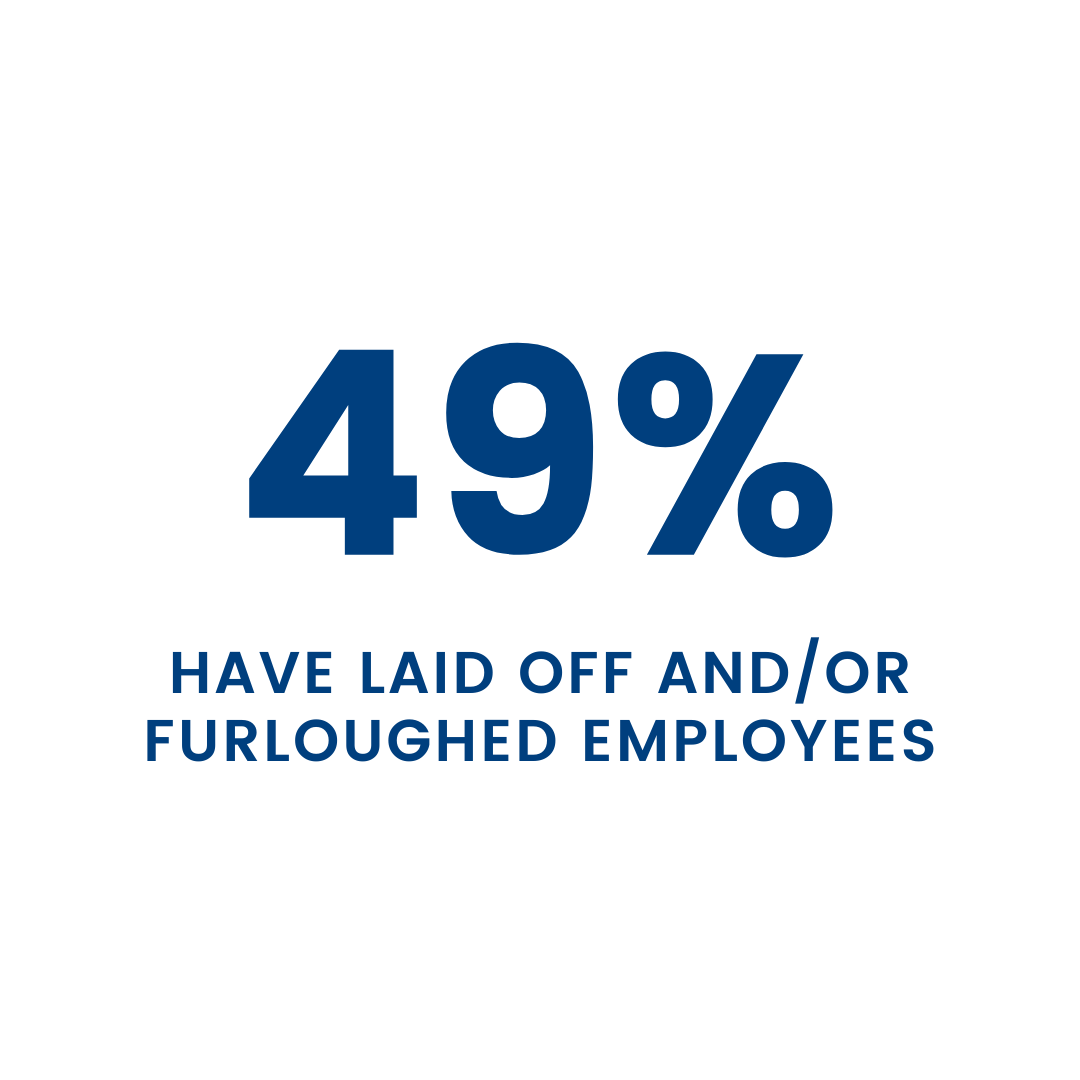

A June 2020 report from the Center for Effective Philanthropy found that COVID-19 and the resulting economic collapse has forced 80 percent of nonprofits to draw upon their reserves. COVID-19 is a reminder that good financial management can be an existential issue for nonprofits, as well as a vital form of due diligence for the communities they serve. Nonprofits are facing a long list of other challenges amid the pandemic: 81 percent have reduced programs or services, 62 percent have reduced staff hours, wages, and benefits, 49 percent have laid off and/or furloughed employees, and 32 percent have taken out a line of credit. All this at a time when more than half of nonprofits report that demand for their programs has actually increased.

EFFECTS OF COVID-19 ON NONPROFITS

While nonprofits across the board have seen an increase in demand for their services, this is particularly true for organizations that serve historically disadvantaged communities – 61 percent of whom have seen a spike in need, compared to 35 percent of organizations that don’t serve such communities. This problem is compounded by the fact that direct service nonprofits have suffered disproportionately amid COVID-19 – 54 percent report that the pandemic has had a significant negative impact on their operations, compared with 29 percent of non-direct service organizations.

Despite the fact that many nonprofits remain critical service providers during the crisis, their ability to deliver these services has been limited – in some cases, dramatically. This problem is especially acute for underserved communities because nonprofits are often in a stronger position to assist them than local governments or the private sector. Many nonprofits have spent years developing relationships on the ground and soliciting support from key stakeholders, handling logistical obstacles in the provision of services, establishing local communication networks, and so on. However, these local organizations often have extremely limited resources – according to a recent report by the National Council of Nonprofits, 97 percent of nonprofits have annual budgets of under $5 million, and many have far less than that (88 percent have annual budgets under $500,000).

Philip Hackney is a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law whose research focuses on the legal relationship between the nonprofit sector and government, and he explains why nonprofits have been stretched so thin: “Nonprofits are being asked to fill roles that they weren’t expected to fill in the past. They’re taking over the provision of services in places where the state has moved out, and this has been happening for 30 or 40 years. In many cases, they’re basically being asked to perform miracles with very little funding.”

Nonprofits are being asked to fill roles that they weren’t expected to fill in the past...They’re basically being asked to perform miracles with very little funding.

Philip Hackney, University of Pittsburg

What does all this mean for the relationship between nonprofits and grantors? Beyond the fact that grantors should carefully assess the impact of any reductions in contributions on the communities their organizations serve (even before the pandemic, nonprofits cited “cutbacks in funding” as one of their top concerns), they should become even more rigorous about tracking nonprofits’ balance sheets, analyzing their fiscal management, and emphasizing accountability in other ways. COVID-19 should be a reality check for the sector as a whole – the status quo of operating on razor-thin margins and trying to get by with just a few months of reserves isn’t sustainable when future economic conditions are so unpredictable.

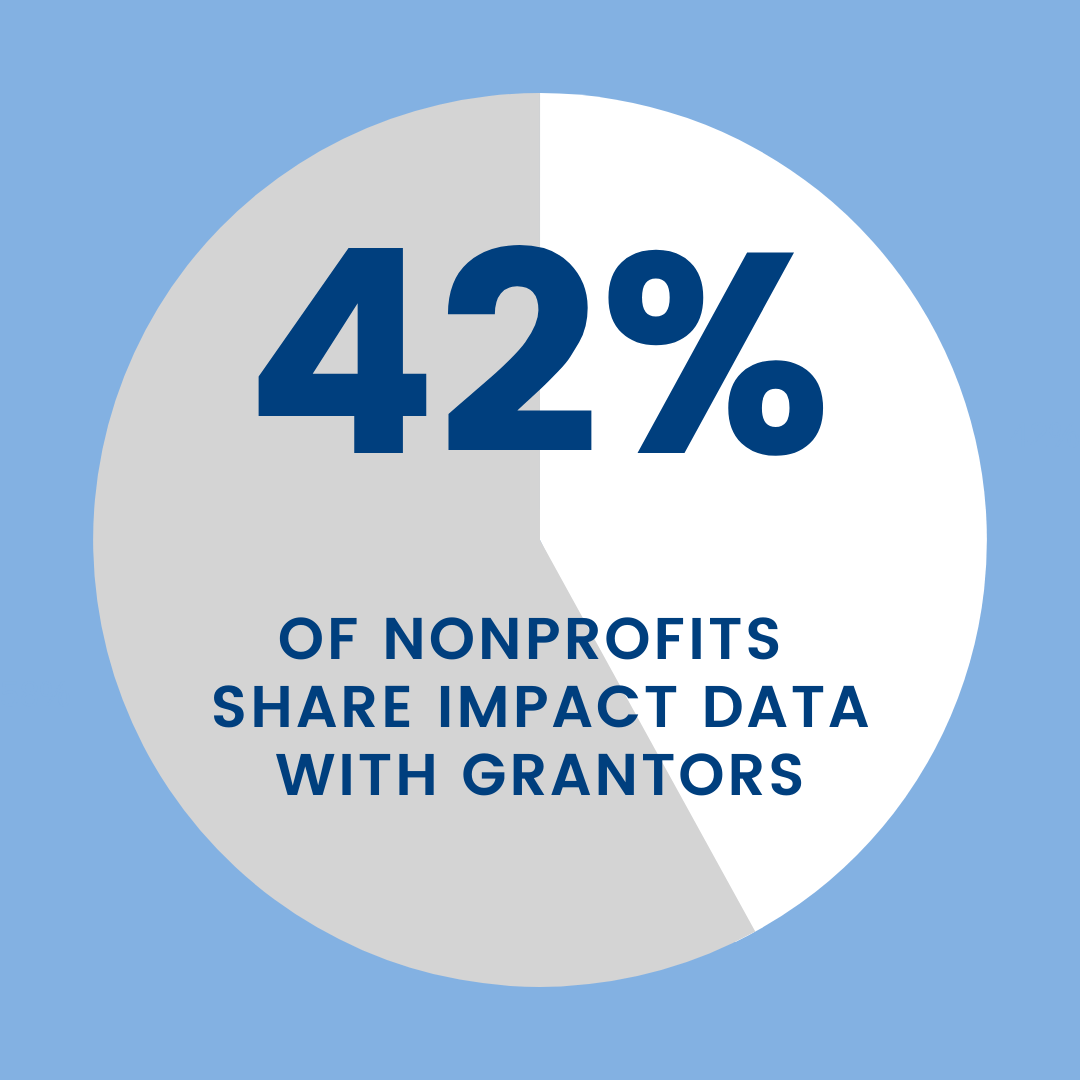

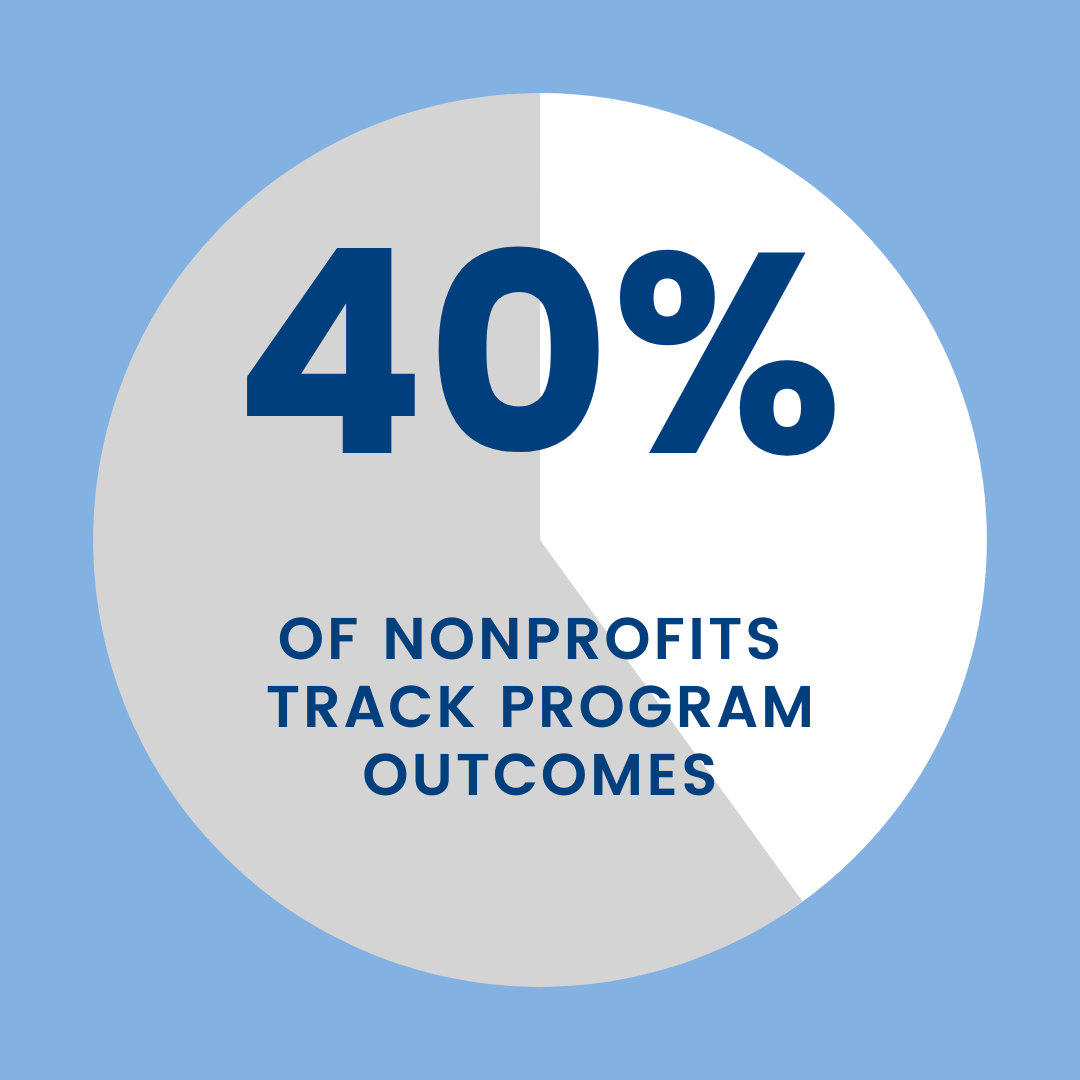

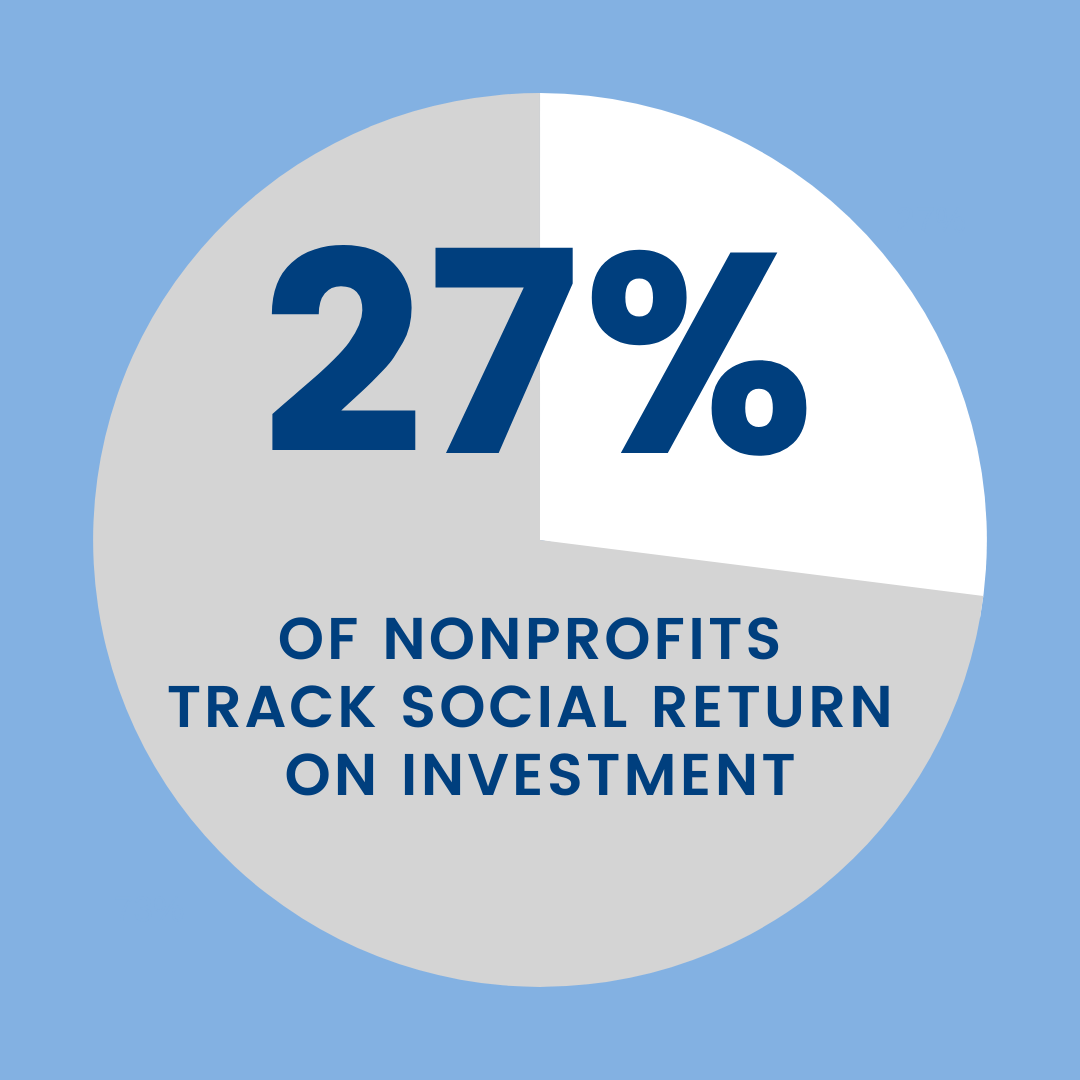

This push for accountability is already underway. According to a 2020 Salesforce survey, 69 percent of nonprofits say the “demand for transparency regarding funding has increased.” However, their actions aren’t in line with this demand: just 42 percent of nonprofits say they share impact data with grantors. Nonprofits are failing to track impact across an array of vital measures: only 40 percent say they track program outcomes, 27 percent track social return on investment, and just over half measure overall mission goals. It’s no wonder that nonprofits aren’t sharing concrete information about impact with grantors – they aren’t collecting that information in the first place.

There are many explanations for this, but almost all of them have to do with a stated lack of capacity to deploy data collection, analysis, and reporting resources. For example, nonprofits say their top three challenges in collecting and sharing information about their performance are:

They have no consistent framework for measurement and recording

They don’t have enough human resources to gather data

They’re incapable of gathering statistics on the impact of programs

With all these perceived limitations, it makes sense that three-quarters of nonprofits describe the process of measuring and reporting impact as a challenge.

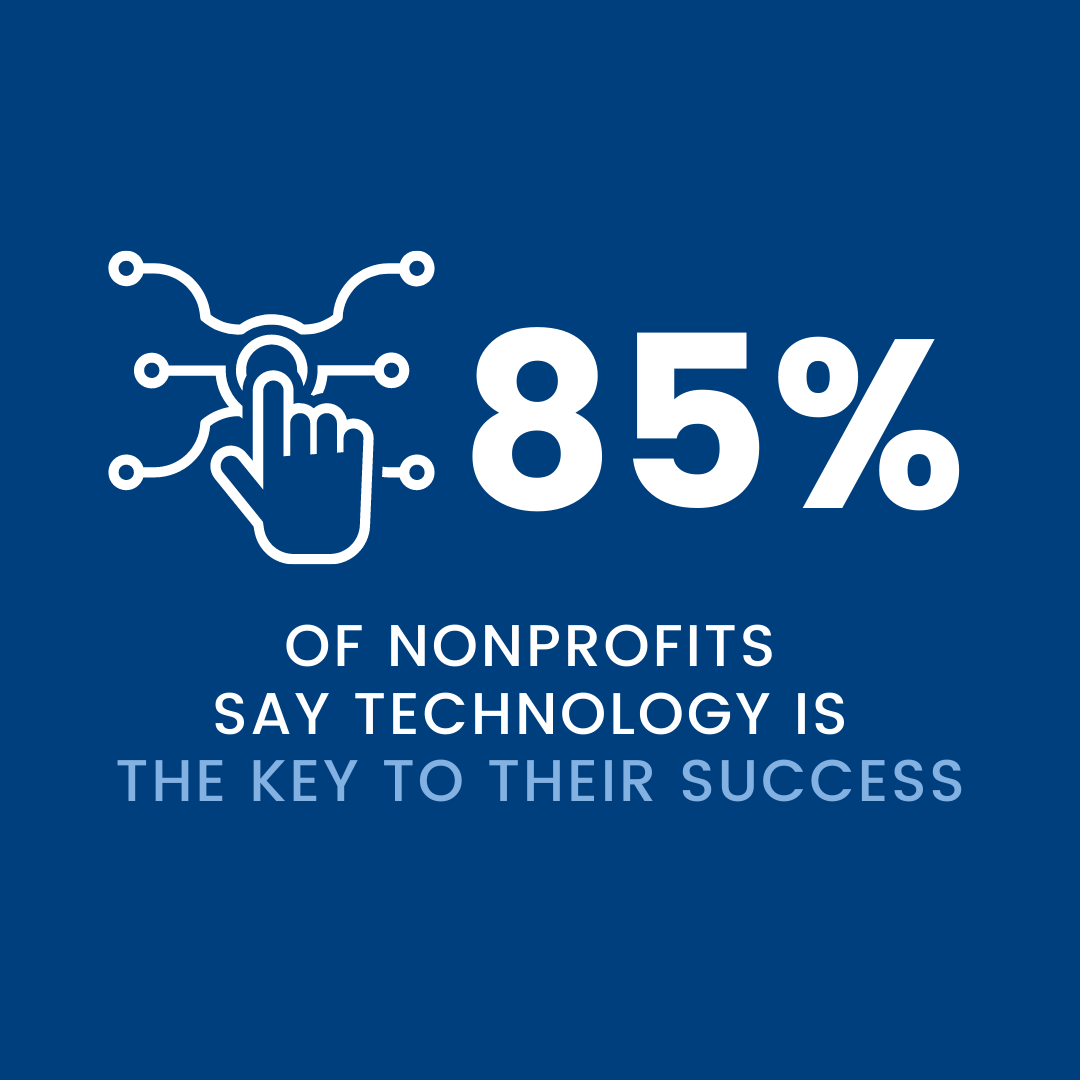

However, there are now sophisticated digital tools that can solve these problems – 85 percent of nonprofits say technology is the key to their success, and it’s far more accessible than they think. There’s a reason we said nonprofits have a stated lack of capacity to deploy data collection, analysis, and reporting resources and perceived limitations on the use of digital tools.

At Resilia, we happen to know there are powerful digital resources available for tracking and reporting outcomes, communicating within the organization and with grantors, and handling an array of other logistical and operational challenges, and those resources can be deployed by any nonprofit, no matter its size.

According to a report by NTEN, just 20 percent of nonprofits consider themselves leaders and innovators in tech adoption, while a NetChange survey found that a meager 11 percent consider their approach to digital resources highly effective. This doesn’t just prevent the assessment of outcomes (and transparency about those outcomes) – it leads to more chaotic and disconnected internal operations, which causes high levels of interdepartmental tension and other disruptions. Hackney points out that “nonprofits often don’t imagine that they should have the same capacities as for-profits, like the latest tech. But as nonprofits take on more and more responsibility in communities, they need to reimagine their roles and what they can accomplish.”

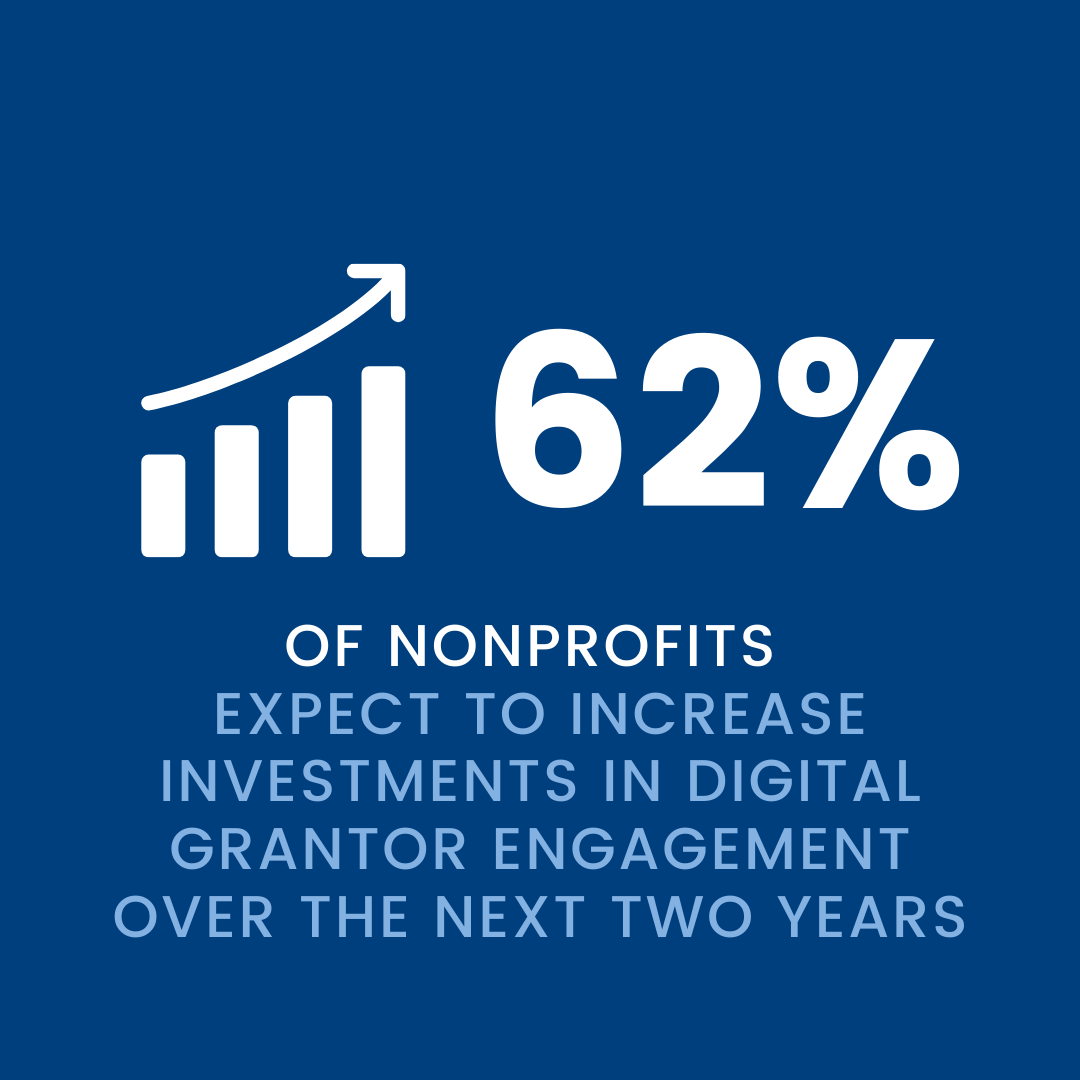

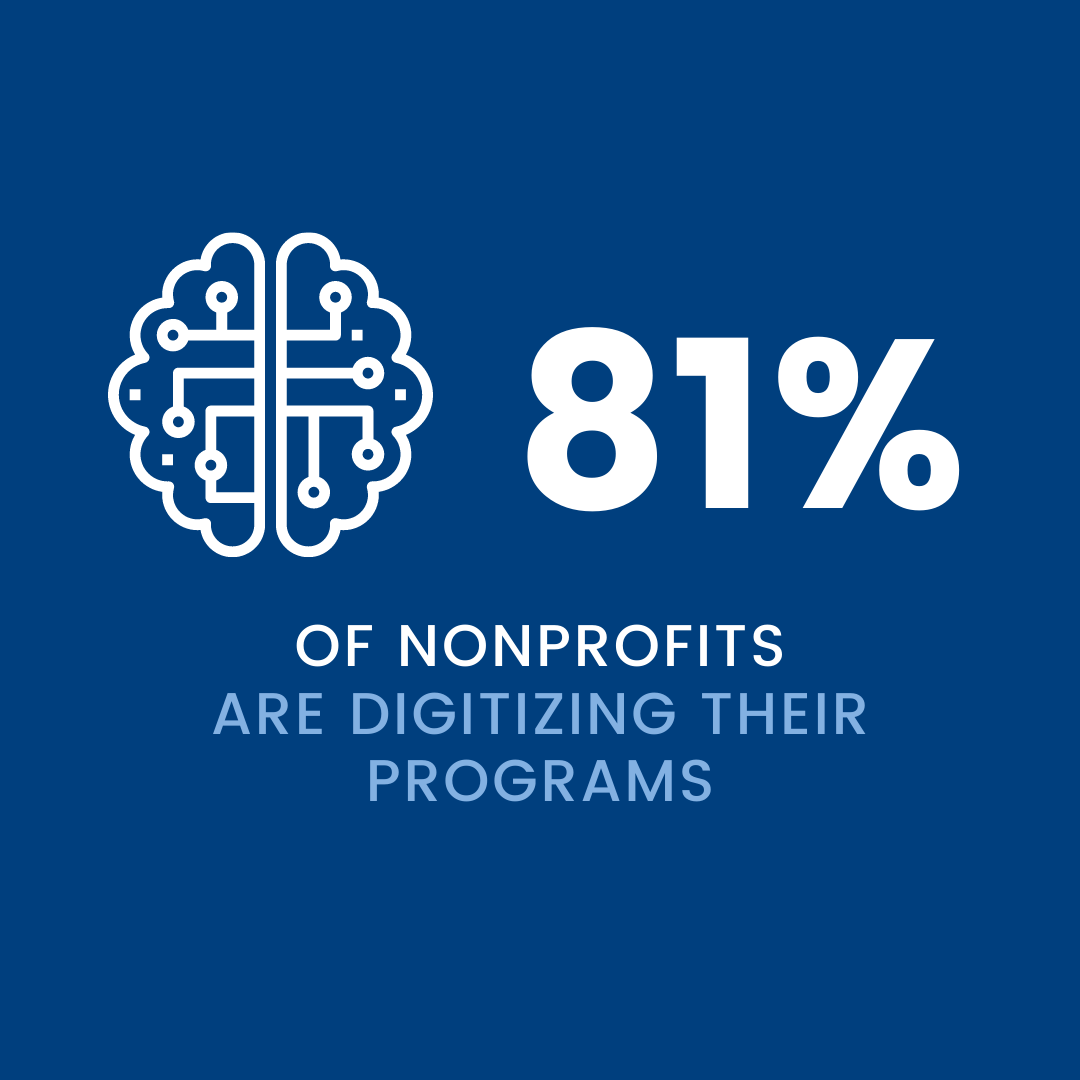

All of that said, there are signs that nonprofits are beginning to take their digital operations more seriously. According to the NetChange survey, 70 percent of nonprofits’ digital teams have been growing, and these teams are reporting directly to the executive director more frequently than they used to. Nonprofits are also increasingly reliant upon digital outreach – a 2020 survey conducted by BWF and Groundwork Digital found that 87 percent of nonprofits expect to increase their investments in digital grantor engagement over the next two years. As COVID-19 continues to keep large swaths of the country locked down, more than 81 percent of nonprofits are even digitizing their programs.

While COVID-19 has put immense strain on the nonprofit sector, it could also spur organizations to take action. It’s one thing to recognize the dangers of having low (or nonexistent) cash reserves in the abstract, but it’s something quite different to face the prospect of laying off employees, scaling back or eliminating programs, and even closing down for good. Although nonprofits were already working to improve their digital operations, COVID-19 has turned this into an urgent need instead of a distant goal.

The relationship between grantors and nonprofits has never been more important, and this is an area where technology will be the crucial differentiator in the coming years. This isn’t just because nonprofits need to be capable of communicating and collaborating with grantors in this time of crisis. It’s because the nonprofits that will be in the strongest position to manage the next crisis are the ones able to secure ongoing grantor support by demonstrating that they’re managing their capital responsibly and delivering on their mission, making wise investments in staff, technology, and programs, and able to gather and provide evidence for all of the above.

Part 2:

How are grantors managing capital?

COVID-19 hasn’t just forced nonprofits to face a few hard realities – it has led to a similar moment of reflection and reassessment for grantors. From difficult decisions about how they will help nonprofits get through one of the most painful periods they’ve faced in decades to overdue reconsiderations of how their partnerships with these organizations should function, grantors are in the middle of a transitional period that will determine the shape of the nonprofit sector for many years to come.

However, the first order of business is ensuring that nonprofits can get through the next year – or even the next few months. On this front, grantors are adopting innovative strategies to provide emergency support. For example, the Ford Foundation recently announced that it was borrowing $1 billion to increase support for the nonprofits it funds. Four other major foundations followed – the MacArthur Foundation, W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, pledging a combined $725 million.

The Ford Foundation believes an influx of grant money is necessary to help nonprofits get through the unprecedented crisis they’re confronting. By financing its increased contributions with 30-year and 50-year bonds, the Ford Foundation is doing something practically unheard of in the sector – taking on debt to support its nonprofits. It hopes this will encourage other foundations to do the same, while convincing companies and other organizations to purchase its bonds as a form of impact investing.

According to a June 10 article in The New York Times (“Leading Foundations Pledge to Give More, Hoping to Upend Philanthropy”), these contributions “could shatter the charitable world’s deeply entrenched tradition of fiscal restraint during periods of economic hardship.” Foundations often don’t pay out much more than the 5 percent of their endowments they’re required by law to distribute, and many of them become even less likely to make these distributions during an economic downturn (as their portfolios, which are tied to the performance of the market, are already in worse shape). The issuance of bonds is a way to circumvent this problem, as the accumulated interest will likely be outweighed by the returns on endowments’ existing investments over the years. Although several major foundations agreed to follow Ford’s lead or have announced similar grantmaking expansions, many others refused.

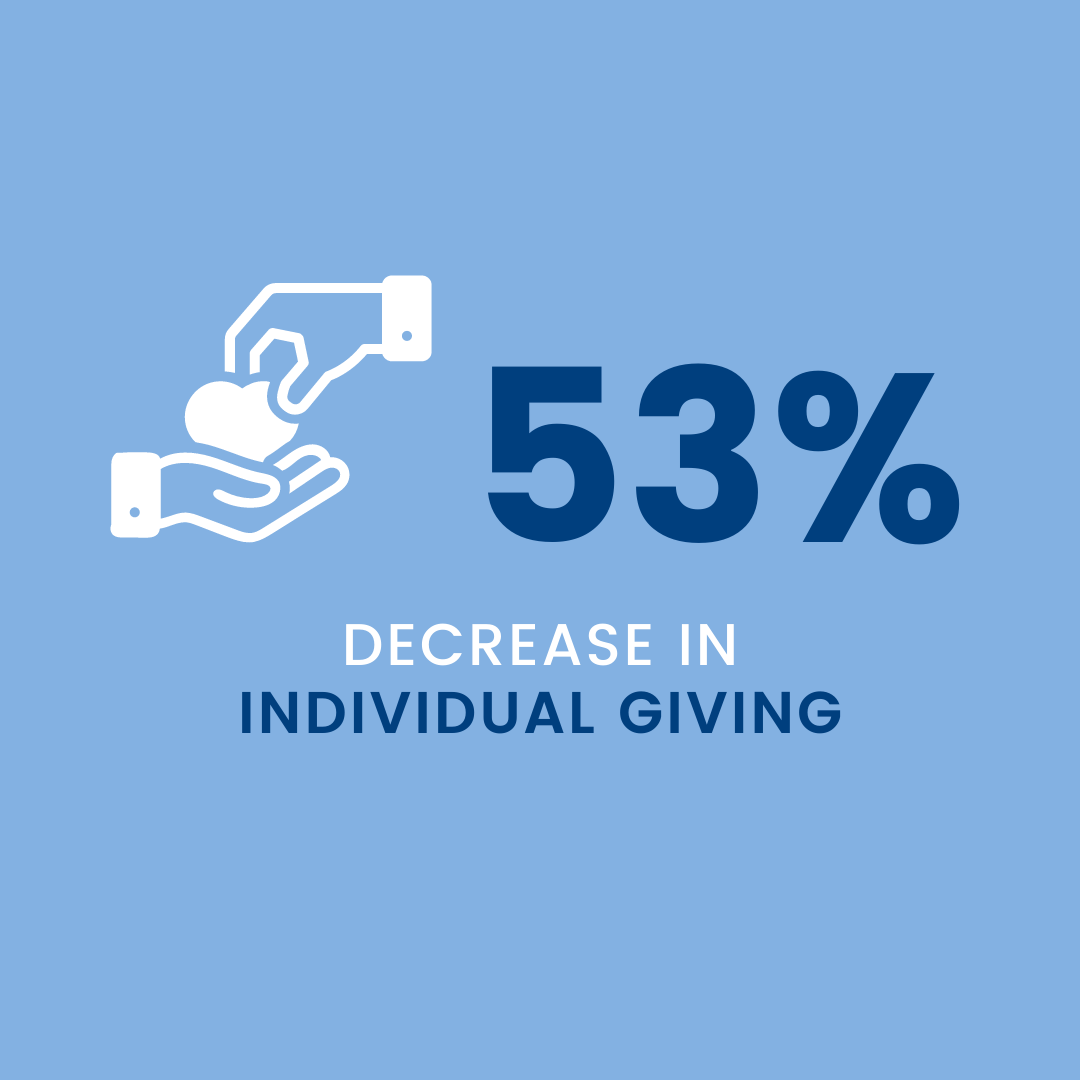

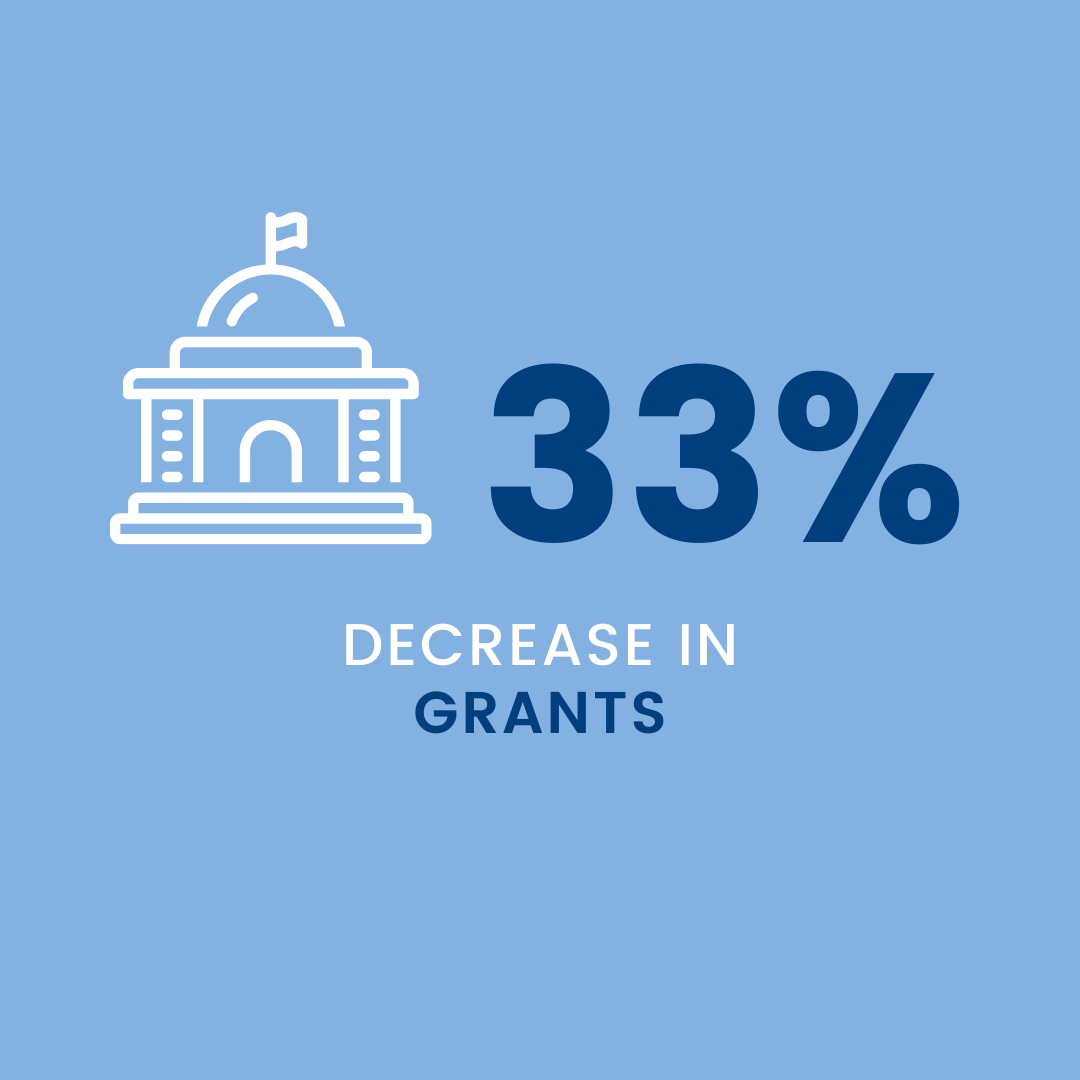

The fact that some of the largest and most prestigious foundations in the United States are willing to fundamentally alter how they fund their nonprofits is a testament to the impact COVID-19 may have on larger trends in the sector. Although the effort to change the norms around how funds are allocated is a positive development, many nonprofits are reporting that their income has collapsed amid COVID-19. According to a recent survey conducted by Independent Sector and Ernst & Young, nonprofits saw decreases in earned revenue (83 percent), individual giving (53 percent), and grants (33 percent).

Nonprofits employ 12.3 million workers, which ranks the sector alongside major industries like manufacturing and significantly higher than construction, professional services, and other large segments of the economy. Moreover, nonprofits have an economic multiplier effect, as they alleviate poverty, provide care for children and seniors (thereby reducing the burden on working families), and address other social problems in communities.

One potential effect of COVID-19 should be a reconfiguration of the relationship between nonprofits and governments.

These are just a few of the reasons why one potential effect of COVID-19 should be a reconfiguration of the relationship between nonprofits and another critical category of grantors: governments. Government grants and contracts account for almost a third of nonprofit revenue, so the nature of this relationship has vast implications for the health of the sector as a whole. But despite the fact that governments around the country rely on nonprofits to deliver services, coordinate and execute their responses to crises like COVID-19, and work to alleviate long-term problems like crime and homelessness, they often make life unnecessarily difficult for the organizations they partner with.

Governments often fail to reimburse nonprofits for the indirect costs they accrue over the course of a project. According to a 2019 report by the Bridgespan Group, “While state and local governments granting federal money are supposed to provide a minimum reimbursement rate of 10 percent, actual indirect-cost allowances are often lower and sometimes nonexistent.” It’s no wonder that 90 percent of respondents to a 2018 survey by the Nonprofit Finance Fund reported that they thought they were being underfunded by government grantors.

Governments also impose onerous application and reporting requirements on nonprofits. A report by the National Council of Nonprofits lists a few of these requirements:

Duplicative submissions and audits

Broken online submission processes

Pointlessly complex applications

Inconsistent compliance procedures

Retroactive demands for information

These are all areas where nonprofits’ reluctance to adopt new technologies is a major hindrance – even if governments don’t take the lead in streamlining their application, reporting, and compliance processes, nonprofits can use digital platforms (like Resilia’s) to standardize their information management. This way, instead of appealing to governments to improve their processes, nonprofits will have a set of turnkey digital resources that can be deployed immediately.

Nonprofits and governments should work together to evaluate what resources a project is like to require at the outset and produce contracts that incorporate indirect costs. At this stage, nonprofits should be as honest as possible about the costs they will likely incur, the length of the project, and so on – if unrealistic expectations are established at the beginning, organizations will have to cut corners and absorb unnecessary financial burdens.

"Underreporting can result in lack of knowledge of the costs of conducting business, impeding clear strategic decision making for nonprofits and funders alike.”

Bridgespan

And these aren’t the only consequences – as the Bridgespan report explains, “In practice, underreporting can result in lack of knowledge of the costs of conducting business, impeding clear strategic decision making for nonprofits and funders alike.”

Hackney observes that there “isn’t enough perspective about the reality on the ground, which is why conversations between grantors and grantees need to encompass the full range of costs. If grantors are making an investment in an organization, they want it to be successful, right? So they should honestly assess what the organization is going to need to get the job done.”

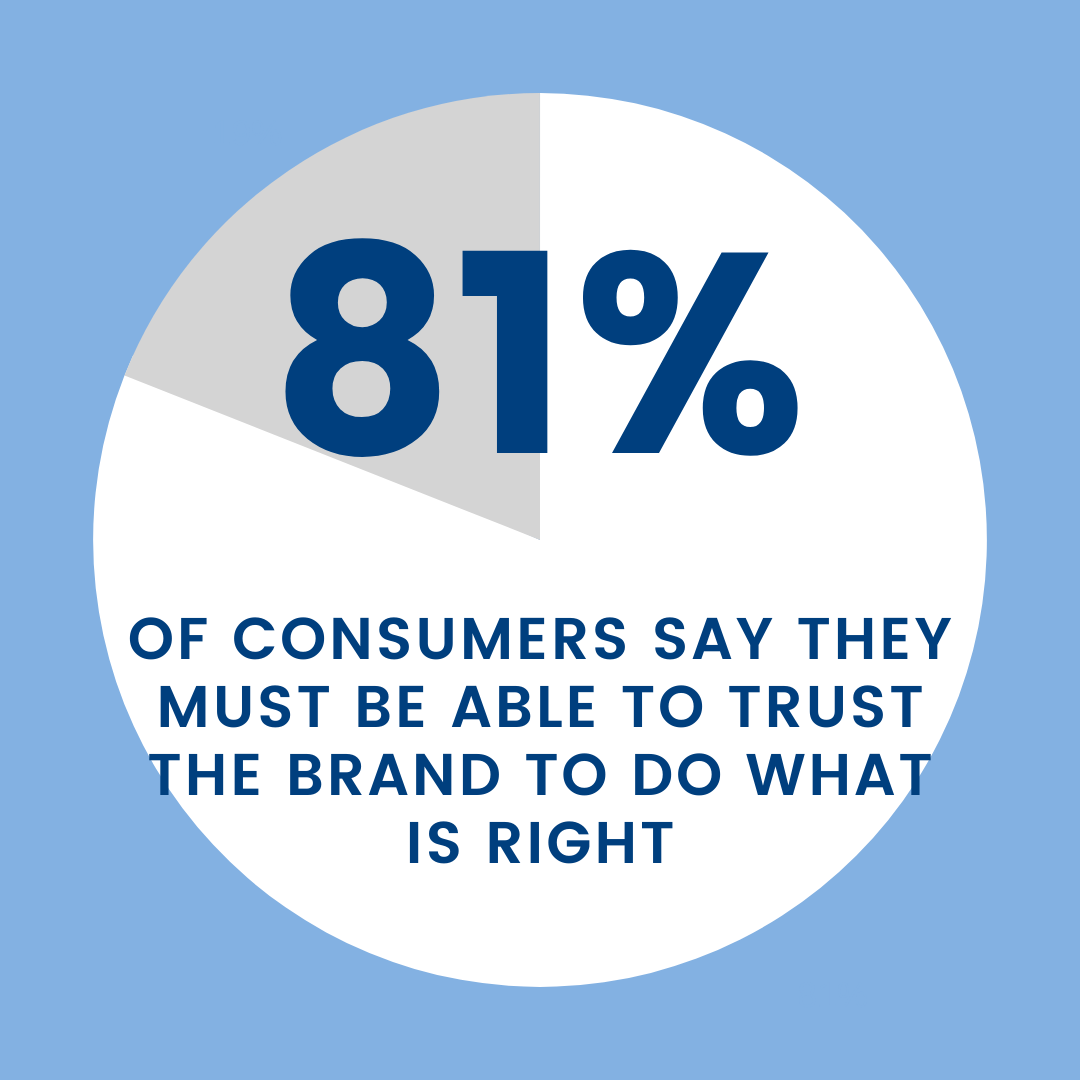

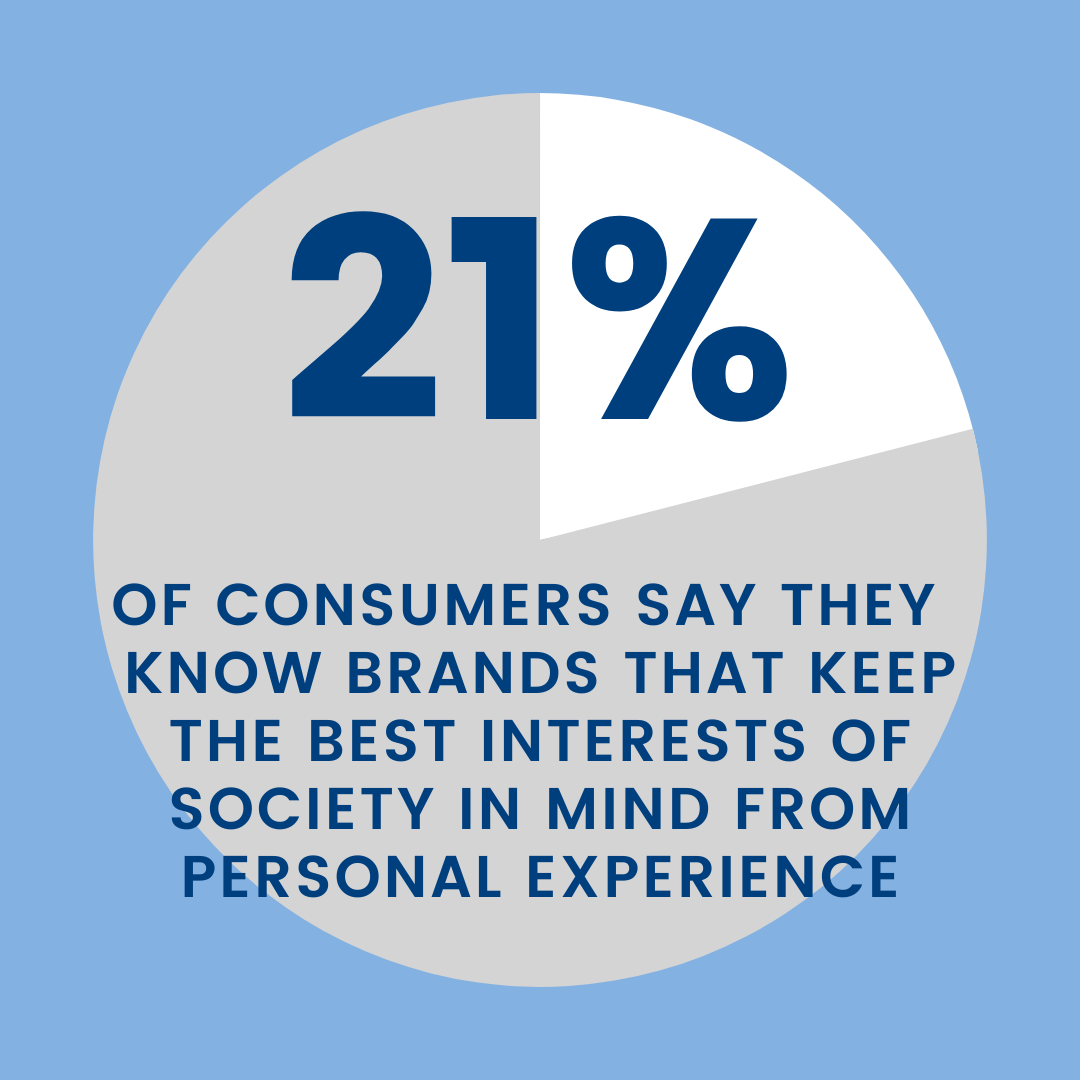

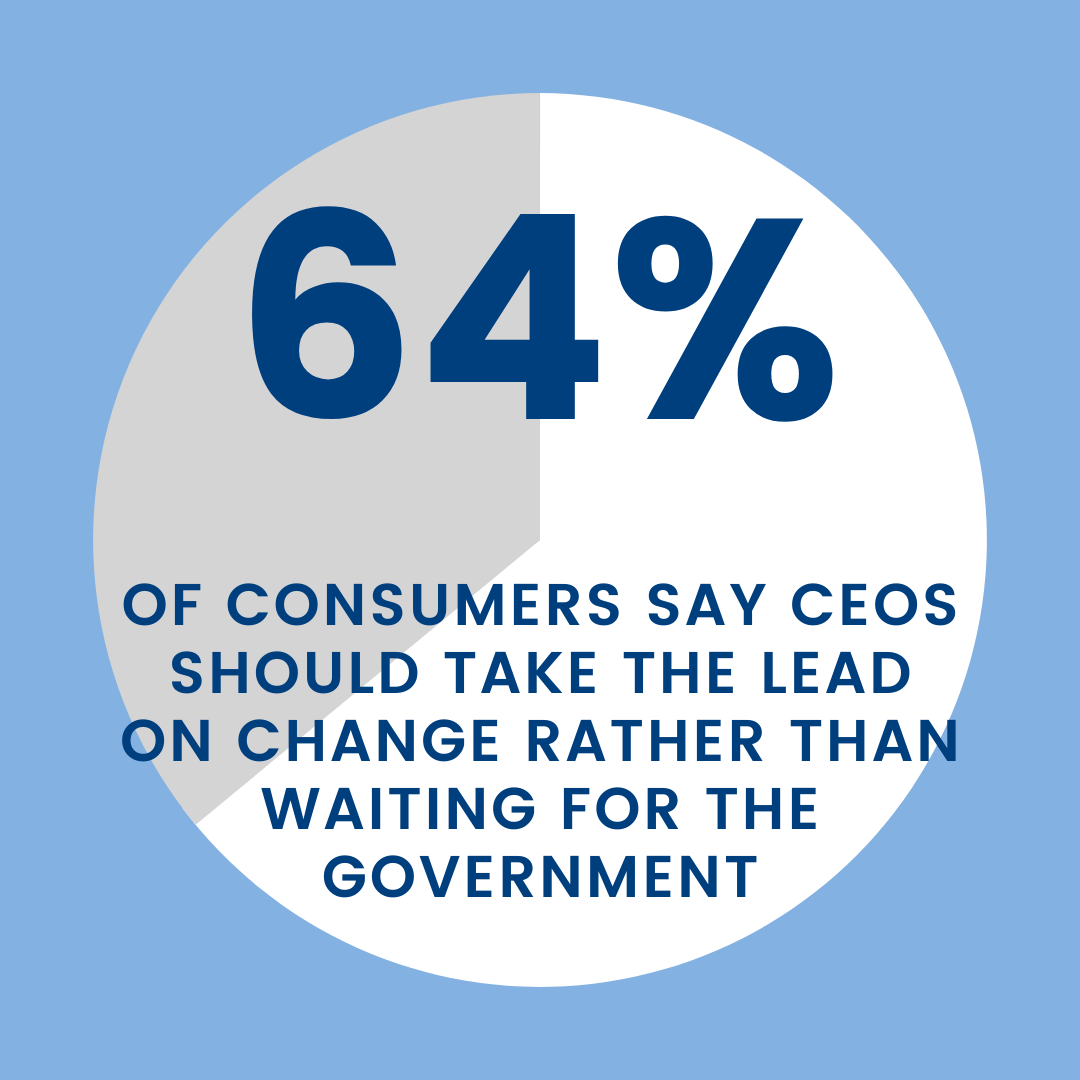

Over the past few years, giving by corporations consistently increased annually: by 5.7 percent in 2017, 2.9 percent in 2018, and 11.4 percent in 2019 (all of these figures are adjusted for inflation). This trend will likely continue in the coming years, as consumers become increasingly concerned about whether brands reflect their values, care about corporate social responsibility, and take action on issues that matter to them. According to a 2019 report by Edelman, 81 percent of consumers say they “must be able to trust the brand to do what is right.” However, only 21 percent say they “know from personal experience that brands … keep the best interests of society in mind.” According to a 2018 survey, 64 percent of consumers now classify themselves as “belief-driven buyers,” and the same proportion say “CEOs should take the lead on change rather than waiting for government to impose it.”

BRAND VALUES & SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

The private sector has every incentive to take more concrete steps toward enacting social change. This is especially true at a time when COVID-19 continues to tear through the United States and in the aftermath of the tragic killing of George Floyd. As protests of Floyd’s killing have swept the country, dozens of companies – including Google, Apple, Walmart, Target, and Nike – announced that they would be making substantial donations to organizations such as the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Equal Justice Initiative, and American Civil Liberties Union. We’re encountering a level of social upheaval and distress which the United States hasn’t seen in decades, and this period happens to coincide with the emergence of a new set of norms and expectations among consumers about the responsibility brands have to contribute.

Grantors’ attitudes toward the deployment of capital are shifting. Foundations are recognizing the need to step up in a time of crisis and increase their overall contributions, governments are seeing the consequences of their inefficient and often unfair relationships with nonprofits, and companies are using their resources to support the causes consumers care about. Now is the time for nonprofits and grantors to take full advantage of these developments and figure out how they can make their relationships as productive and high performing as possible.

Part 3:

How Grantors and Nonprofits Can Work Together to Maximize Impact

While COVID-19 has been an unprecedented pressure test for nonprofits, as the sector moves toward greater transparency, accountability, and collaboration, it will be in a much stronger position to face future crises and scale impact as much as possible.

Too many nonprofits are convinced that they don’t have the digital resources or expertise to track and report outcomes, but this isn’t true. Sophisticated data collection and analysis tools have never been more accessible, and platforms like Resilia’s can open up channels of communication between nonprofits and grantors that ensure the project scope remains consistent, payments are made on time, compliance processes are streamlined, and outcomes are clearly communicated. However, nonprofits have some work to do before they’ll be able to implement technology effectively – 45 percent of organizations say a “lack of flexibility for organizational change prevents departments from using tech to improve strategy.”

Transparency leads to accountability. Nonprofits have to be capable of demonstrating the tangible impact of their programs – there’s no other way for grantors to determine whether or not an organization is worthy of support. Grantors also need to know what financial constraints nonprofits face, what resources they have, and how they’re managing those resources. This will help them make informed, targeted investments while encouraging nonprofits to be more accountable for their financial management.

In recent years, there has been a shift away from using overhead as a major measure of nonprofit performance. An open letter published by GuideStar, Charity Navigator, BBB Wise Giving Alliance observed that the “percent of charity expenses that go to administrative and fundraising costs – commonly referred to as ‘overhead’ – is a poor measure of a charity’s performance. We ask you to pay attention to other factors of nonprofit performance: transparency, governance, leadership, and results.”

People often chop a nonprofit down a notch because its overhead is too high, but this perspective often has it backwards.

Philip Hackney, University of Pittsburg

Hackney echoes this point: “People often chop a nonprofit down a notch because its overhead is too high, but this perspective often has it backwards. If anything, nonprofits don’t spend enough on administration, the implementation of new tech, and so on. This makes it harder to generate dollars and execute your mission down the road. In many cases, nonprofits need to rethink what their services are worth and focus on self-respect – if investing in human capital or new technology will improve their programs, those are investments worth making.”

Accountability doesn’t just go in one direction. Nonprofits should also demand transparency from grantors about project timelines and payment schedules, the level of support they can expect to receive and for how long, and other issues that have a direct impact on their ability to plan and execute programs. The failure to reimburse nonprofits for all the costs they incur isn’t a problem confined to governments – all grantors struggle to account for the full range of costs associated with the projects they support. Just as grantors can help nonprofits run more smoothly and achieve better outcomes by asking for specific information about management, program performance, etc., nonprofits can help grantors make better-informed decisions about which projects to take on and how to execute them.

The nonprofit sector is built on collaboration – between nonprofits and grantors, organizations and the communities they serve, and so on. There’s also collaboration between grantors themselves – as demonstrated by the Ford Foundation’s recent effort to push other foundations to increase their contributions. This effort was a success – not only did it encourage other foundations to commit hundreds of millions of dollars in additional funding, but it also changed the conversation about how much foundations should be contributing in general.

Nonprofits and grantors also have a renewed focus on racial inequality in the United States, which was laid bare once again with the Floyd killing. Beyond the influx of attention and contributions from the corporate sector, large philanthropic entities are investing in organizations and initiatives like Campaign Zero and Color of Change to address issues like police brutality and other forms of inequality. Meanwhile, there has been a push at the local, state, and federal level to develop new solutions to crime that deemphasize the role of police, incarceration, etc. and promote the work of nonprofits that focus on addressing poverty, inequality, racism, homelessness, mental health, substance abuse, and other issues that lead to crime. It isn’t often that the entire country is focused on a set of vitally important issues like racial inequality and police violence all at the same time, which is why the nonprofit sector should seize this moment to seek partnerships that will scale impact as much as possible.

It isn’t often that the entire country is focused on a set of vitally important issues like racial inequality and police violence all at the same time, which is why the nonprofit sector should seize this moment to seek partnerships that will scale impact as much as possible.

For example, members of the Minnesota Council on Foundations have forged a wide range of partnerships to help communities recover after the unrest, combat racism, reform police departments, provide loans and other forms of assistance to businesses and nonprofits run by people of color, improve equity and representation in local businesses and organizations, and address many other drivers of inequality. One of these initiatives is the Twin Cities Rebuild the Future Fund, in which the Greater Twin Cities United Way, The Minneapolis Foundation, and the Saint Paul & Minnesota Foundation are working together to provide immediate support to minority-owned small businesses, many of which sustained damage or were destroyed in the unrest. When organizations pool their resources, they can get help to members of the community who need it more quickly and ensure that services aren’t being duplicated.

There are 1.56 million nonprofits in the United States, and (as noted in section one) the vast majority of them operate on annual budgets of less than $500,000. With so many small organizations on the ground in just about every city in the country, the importance of collaboration couldn’t be clearer. Amid COVID-19, the worst economic contraction since the Great Depression, and historic protests of racial injustice, it’s no surprise that nonprofits are reporting surging demand for their services. However, this means the nonprofit sector is under pressure like never before – reserves are drying up, employees are being furloughed, programs are being cut, and the need only continues to rise.

Democratize philanthropy. We have to bring in systematically disempowered communities and give them a real voice in where philanthropy is going.

Philip Hackney, University of Pittsburg

This is a time for cooperation in the nonprofit sector. Giving by foundations increased in 2017, 2018, and 2019, and as the Ford Foundation demonstrated, it’s possible to convince large organizations to jointly increase their contributions during a crisis (something foundations have historically been loath to do). There should be more collaboration of this kind among grantors in general, which could take the form of mutual pledges to address the problems outlined in this report. State and local governments are also on the lookout for organizations to partner with as they respond to COVID-19, and they should explore potential collaborations with nonprofits of all sizes. But nonprofits have to do everything possible to demonstrate the effectiveness of their programs (as well as the efficiency of their operations) if they want to secure contracts with foundations, governments, and all other grantors.

Finally, nonprofits and grantors alike have to focus on stronger relationships with communities themselves. According to Hackney, it’s time to “democratize philanthropy. We have to bring in systematically disempowered communities and give them a real voice in where philanthropy is going.” The first step for any successful program is reaching out to stakeholders across a community, listening to their concerns, incorporating their feedback, and building trust. The nonprofits and grantors capable of doing that will always have the greatest impact.

KEY TAKEAWAYS FOR GRANTOR AND GRANTEE CAPITAL ALLOCATION

1

It’s clear that many nonprofits face a series of operational issues that need to be addressed if they want to have healthy long-term partnerships with grantors. Nonprofits shouldn’t allow themselves to remain stuck in a perpetually risky financial position – a perennial problem that COVID-19 has turned into an immediate crisis. While nonprofits are indispensable for delivering services to underserved populations around the country, they also have to be held accountable. Grantors and nonprofits should continue to convene and support their communities, train and educate team members, establish clear goals and measures of progress, and rigorously assess their performance.

2

At a time when nonprofits are facing an unprecedented (and in many cases, existential) crisis, grantors have to step up to offer emergency support. This is why the Ford Foundation has decided to take on debt to assist its nonprofits: a move that has catalyzed similar efforts from other major foundations and could lead to a reassessment of how much they contribute going forward, or a larger reevaluation of the 5 percent minimum distribution requirement. Now is the time for other grantors to rethink their relationships with nonprofits as well, such as governments, which often fail to fully reimburse organizations for their services and impose needlessly complex and inefficient logistical constraints on them. Meanwhile, as corporate giving continues to rise and consumers increasingly expect brands to reflect their values and take action on social issues that matter to them, nonprofits will likely form more and more partnerships with the private sector in the coming years.

3

The major challenges of 2020 (from COVID-19 to the protests for racial equality) have called upon nonprofits and grantors to seek new ways to pool resources and address issues we all face. Whether it’s governments working with nonprofits to raise funds and deliver critical services or cooperation among grantors that recognize the importance of helping organizations struggling in extraordinary circumstances, it’s clear that partnerships across the sector can scale impact in an immediate and dramatic way. However, for these partnerships to work, nonprofits and grantors will have to be more transparent about the terms of their relationships and willing to hold themselves accountable. This is the only way to build sustainable, long-term partnerships that will endure as the sector navigates this crisis and whatever the future may hold.